African & Black Creatives for Development, and SELDI, SEVHAGE presents the winner of the SEVHAGE/Maria Ajima Prize for Creative Non-Fiction 2023. Abasi-maenyin Esebre’s piece is the winning entry and a unanimous choice of the judges for its beauty. – SVA

1.

It’s neat to think that death belongs to the old, to hope that the future will accept prayers as bribes to protect our young and their ambitious dreams, but just as some sunsets coincide with the moon, some children get epitaphs before their parents’ hair turns grey. To us, this truth seems cruel and unfair; no, it feels gut-wrenching and debilitating, a reality with the power to induce psychosis or make one beg for instant death, for the earth to do to us what wicked thing it has done to our hapless children. Yet, our tears go unanswered; they fall on barren soil. And like children who believe mistakenly swallowed orange seeds, drawing oxygen from their lungs and nutrients from their liver, will force a tree to sprout in their bellies, we weep, but we weep and weep in vain.

2.

In the middle of the night, my mother received a call from an unknown number. She let the phone ring out for a few seconds. It was the matron from my younger sister’s all-girls school, Holy Child, on the other end of line: Ima was sick. The next day my parents arrived early at the school. Ima could barely walk to the car. Her hip had swollen, revealing a visible lump which forced her to wince with each treacherous limp she took.

3.

Months prior, during the long break, she’d complained about a recurring ache in her left hip. When my parents inquired if she knew what could’ve led to it, she nodded.

4.

One evening, during prep, a classmate who’d gone to pee crashed into the hall: she’d seen a ghost. All the girls panicked and scampered out of the classroom. In their struggle to make it to the door, a girl shoved Ima from behind, sending her hip-first into a desk’s diagonal edge. Adrenaline pumping, my sister rose to her feet and darted out with the other girls towards the hostel where the matron brought them to an abrupt halt.

Two weeks later, a sharp pain would jab at Ima’s hip, again and again, like waves taking more and more sand away from the beach with each successful retreat.

But on that night, under the moon, she and her friends mocked each other’s panicked response, which they exaggerated in dramatic recreations—happy and out of breath, happy and full of life.

5.

On December 26, 2019, before COVID shook the world, Ima died.

6.

It’s said that it takes an entire village to raise a child; but, it also takes a village to bury a child. Or it should, at least. However, when my parents went to bury my sister, Ima, the village youths demanded for alcohol drinks to be bought. They confronted my parents, asking why they would dare to conduct a burial without first organizing a funeral, where the community could come and eat and drink.

Ndisme á wák gü utö is the örö phrase that came to mind when my mother relayed this event to me. Because, truly, rubbish does come in different forms. Insanity, too, must be assorted for such an uncouth attitude founded on greed and a total lack of empathy in the name of tradition to rear its ugly head in such a vulnerable moment. It’s funny to imagine such callousness in the face of grief, to be met with such heartlessness while your heart is still in the middle of breaking. My mother cried as she grabbed one of the men’s shirts and had to be dragged aside by some relatives—who’d helped clean my sister’s corpse—for her to cool off.

7.

Ima hated the Chinese medicine prescribed to her by a doctor my dad consulted. The syrup, a mustard, mucilaginous colloid, which she measured into a glass cup and took with a tablespoon, had an astringent taste—like lime mixed with vinegar which made her lips pucker. She couldn’t do it herself. I dropped my phone on the couch and took the spoon from her.

“Oya, my oga,” I hailed her.

She giggled as she opened her mouth and took the first spoon. I hailed her some more; her mouth frothed with laughter when I gave her the next spoon. We repeated this routine again and again until she was practically holding her belly as her laughter spiralled into a raucous cackle. As I flew the final spoon like an areroplane before bringing it to her mouth, she laughed her head off. After gulping down the last spoon, she lay on the ground, laughing an airless laugh which I joined until my belly began to ache. I didn’t see it then, but now I’m convinced: she needed the laughter more than she did the medicine.

8.

After the third surgery to remove the tumour that returned more vigorous than the previous two times, the doctors diagnosed Ima with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare type of cancer that affects the tissues and bones of children.

9.

We were confounded at home; the verdict came across as implausible—from a hip rammed against a desk to three surgeries and Ewing’s sarcoma. We—my brother and I—underestimated the severity of the situation or we didn’t quite understand how much pain Ima was in because she managed it well in the beginning, before things got worse. The articles we read online informed us about malignant cells and metastasis, which the doctors confirmed had already occurred, but they didn’t prepare us for the onset of chronic pain. They didn’t prepare us for blood streaming down her leg from the hip at random hours, leaking through the gauze spread over the wound which refused to heal. They didn’t prepare us for my sister waking up in the middle of the night screaming as her meds wore off. They didn’t prepare us for the tears she cried, the way she begged God for death, the way she scratched her hair as the pain clawed at her insides.

My sister grew hollow. She abandoned her hobbies—reading books and gossiping with my brother. Chatting with her friends no longer sufficed; she couldn’t even muster strength for any prolonged interaction. The arpeggios of the song I played for her—the beginning of which sounds like the first three notes in City of Stars, a soundtrack from Damien Chazelle’s La La Land—no longer acted as an analgesic. The pain had broken its off switch.

All we could do at home was offer apologies round the clock, each taking a turn at sorry, in the hopes that the comfort would soothe her.

That night we argued about our next move. I suggested chemotherapy; my parents remunerated the doctors’ prognosis and the final blow—Ima had been diagnosed with fourth stage cancer. At our wit’s end we took her to a church. Failed by science, we sought spiritual intervention.

10.

The head pastor was a spirited old man whose eyes had a tangible clairvoyance to them; however, the prophet, a young man in his mid-thirties who prayed for my sister, often screamed until his baritone voice thinned into an inaudible whistle. He prayed, in an attempt to break the spell he said had been cast by my uncle: the ghost my sister’s classmates had seen was my dad’s brother. The politics of my extended family comprises stories rife with betrayal, resentment, and hatred which no one can trace to a single event. There are sides, dividing lines drawn with blood that mustn’t be crossed. Our family is a volleyball court with a line of bricks in place of a see-through net dividing both teams. It’s deemed sheer naïveté and dangerous, even, to offer truce. It’s easy to see why the prophecy held water.

When he gave us assignments, desperate for a solution, we obeyed. Months went by, no progress. Ima grew leaner as if her skin was being sucked into her bones. My parents took her to another church. The prophetess in the new church confirmed the prophecy of the first prophet. She asked my mother and sister to stay in the church, next to other ailing people. Ima said the place smells like sewage combined with the acrid smell of burnt plastic. It was in that church my mother scooped my sister’s feces when she could no longer walk. It was here my mother cried and cried when she fell as she stumped her feet on her way to get my sister food from across the street. She cried as my sister noticed her red eye and asked her why she was crying. She cried when my sister begged for death. She cried when she recounted the story to me.

11.

There’s this outré notion that writers tilt their words towards grief like sculptors do towards drapery in their works as an easy way to show mastery of a difficult form. Or the claim that Nigerian writers succumb to grief porn. Maybe it’s why I never wrote about my sister’s death until now.

12.

I woke up from a dream one night with tears in my eyes: I’d been playing with my sister and forgot she was gone.

13.

When my mother returned from the village with my father, face battered, hair tattered, she hugged me so tight I could feel her heartbeat in my own chest. That night, she fainted twice.

14.

My brother and I rarely talk about my sister. He posts her picture on his WhatsApp status on her death’s anniversary.

15.

One day, as I was trying to help my dad check a link someone had sent him, something caught my attention: my sister’s picture, where she’s wearing a green, chiffon dress, is his wallpaper. Anytime he talks about her, his voice echoes with pain.

16.

My sister hated to cook, but she loved to clean. Her handwriting, for her age, was calligraphic. She loved Alvin & The Chipmunks. She wanted to be a doctor and she knew stuff about medicine while still in SS1. She used to place a lighted matchstick on the gas cooker’s plate before turning the knob—she was a lazy genius. She read a 600–page book in less than a day; the same book took me 2 weeks to complete.

17.

There’s a thermostat that goes off once my mother and I dive down to recover mementos of my sister from memory: her laughter, her phrases, the inside jokes she favoured. When this greif detector is agitated, we resort to humour or drown the queuing tears with wishy-washy platitudes: God knows best. Everyone will die.

Anything to keep her memory at bay. Although memories are merely essays—futile attempts at historically accurate recalls, like documentaries that ferment and get transcribed into a different genre, speculative fiction, perhaps—we never stay too long there. We keep one foot outside the exit door. We unwittingly make her absence abstract so we can digest it better. However, grief is silica gel and a broken heart is never not hungry. Everyone in our family is an undertaker with winged feet, yet struggling under the weight of our loss.

18.

One of the assignments the young prophet gave us was to prepare a buffet—my sister had been relegated to eating figs and drinking soursop smoothies only as a remedy for cancer; she felt relief during this period—to buy wine, eat and be merry. We did this, cheering and laughing, chinking wine and what not. The sickness worsened after.

19.

When they pronounced my sister dead, my mother picked her body and tried to slam it on the floor; all the doctors had to rush to restrain her.

20.

Unwilling to conscript us too soon into grief and its invisible gerund, my parents buried our sister without informing us. I haven’t been to my sister’s grave yet. When I visit I don’t know what I’ll do with myself. Maybe I’ll sit and ask if she wants to hear me sing. And I’ll interpret her silence as yes. It’s neat to think so, right?

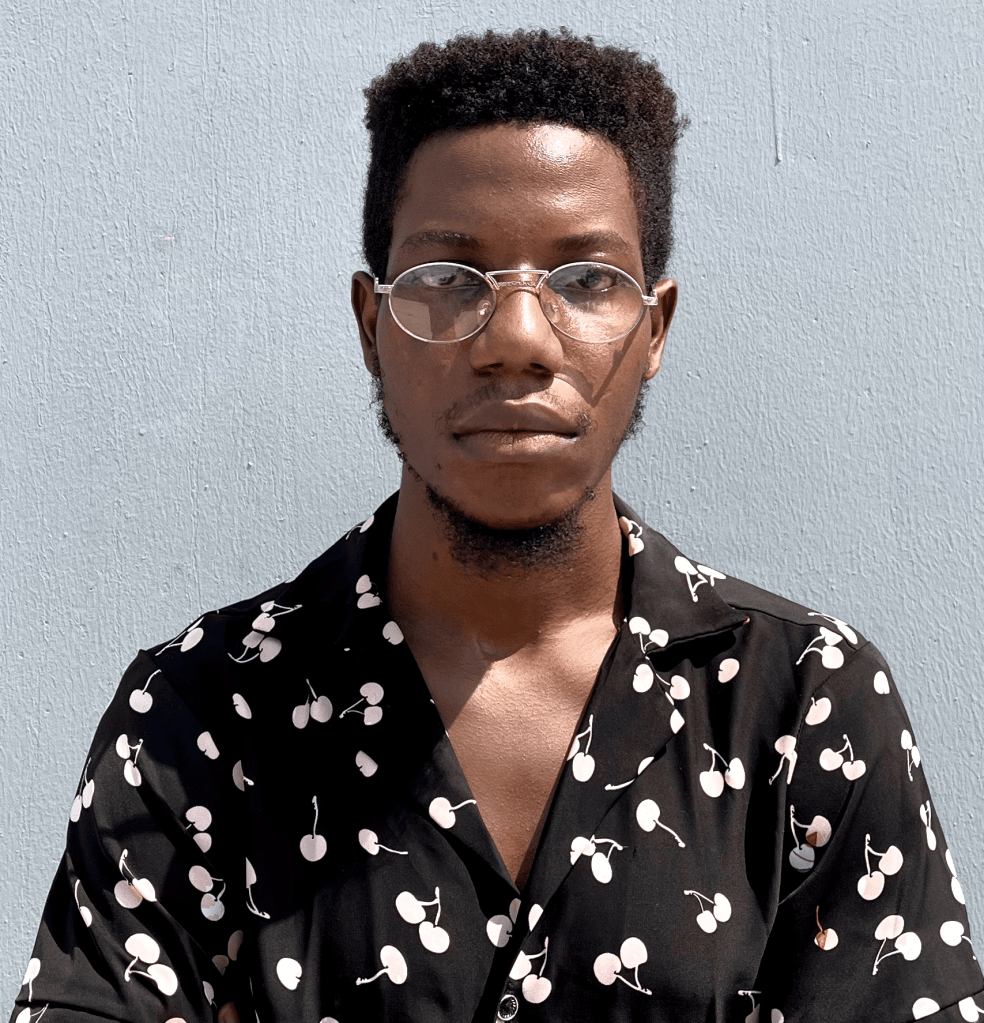

Abasi-maenyin Esebre is an Oron storyteller who centres Calabar, the city where he grew up, in his stories. His essay, Call Me By My Name, was published in AFREADA. He won the 2023/2024 Sevhage Prize for non-fiction with his essay, Grief: Its Invisible Gerund and Compass Rose respectively. His short stories have been shortlisted by Gratia Magazine and ALITFEST in separate competitions. Curious to a fault, he enjoys research in his free time and is an avid reader of both film and literary criticism. Although he enjoys writing books and aspires towards being an author, he plans on making a pivot to his original dream of being an auteur. He runs The Rich Writer’s Manifesto, a blog where he reviews books, and films. You can find him on X (formerly Twitter) @abasimaenyinn

I also lost my brother in 2019 and I haven’t been the same. A part of me died that evening and it hurts that I’ll never get it back. I still cry from my dreams into reality and I know I’m still a long way from healing. They say your learn to live with grief but you don’t. She always comes with a new veil.