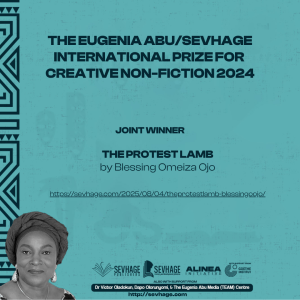

In partnership with Alinea Initiative, Goethe Institut Nigeria, African & Black Creatives for Development, and SELDI, SEVHAGE presents the winners of the Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction 2024. Blessing Omeiza Ojo’s piece is the joint-winning entry.

“And like sheep to the slaughter, we marched—

but not without song.”

— Unattributed

Lamb as a Metaphor

I became a harlot at 10. The reason wasn’t different from what had shoved minor girls, less than teenage years to stand at three-three junction at dusk, in Kubwa. Ragged bump shots and singlets on, but uncovering their body maps. Their fingers with 50cm long artificial fixed nails functioning as a compass, often determine the direction of menfolk. In the name of desire, they offer themselves to anyone interested. A man who would pay twenty-thousand-naira tonight for an hour pleasure, would have to queue tomorrow behind a benevolent man who is willing to triple the fee. Such was my way. I was in search of the real identity of love; for where there’s love, there’s God. And anywhere love surpasses, I go.

In the morning, I could be in a shrine with a spiritualist, consulting my dead parents to know which of my uncles were the culprits and architects of their death. Then, when the sun rises to heat up the uneaten sacrifices of intestines, fresh bones and blood by the gods, to oozing point inimical to my body, I would go pray subha. And when the sun enters its chamber for nocturnal slumber, a neighbour of mine who worships in churches would invite me for a night vigil. I was this faithless, but didn’t tell my grandma who was aware of my disappearances from home. All I wanted was to hear a voice in my head, not induced by my memory of overt speech, saying: boy, you’re loved and safe in my sanctuary; no harm shall befall you. But I’ve never heard. Perhaps, I’m not a child, at least, not a child of God. I bet you, you can’t stand the desire for safety. No one can. We often run to barbicans until they cease on a fateful day, to be what we name them. They’d rather switch into a den of death, and the hands that altered the phenomenon, unseen.

Where I felt I was safe, a man once called me an animal. Animal protein. I didn’t see a knife in his hands, but a Bible. However, his voice was a two-edged sword forged to butcher my hope. In his words: “you all are God’s sheep.” What! Aren’t sheep meant to be slaughtered and eaten? I wasn’t yet healed of the wound in my heart, he said to me who had stood up to ease myself while the service was still on: “O lamb of God, do not stay too long away from this service for the glory of God will shine on his house anytime from now.”

I have, since my childhood, been a witness of lambs’ fate in my country, the glory of death.

Long before I understood protest in banners, chants, or vigils, I had lived it. Quietly, with my body. Every place I turned to for safety, for salvation, demanded its own sacrifice. In the temples and vigils I chased meaning; in the streets, I came to know fear. So, when the Lekki toll gate massacre unfolded on the screens of the nation, I wept not as a spectator, but as someone who recognised the lambs. I knew them. I had been one.

End SARS Protest

The way of the lamb is that of a calm sea, serene and undisturbed, picturesque of the quietude of a world waking into a boneyard. On the outbreak of the news on the night of 20 October 2020, at about 6:50 p.m., that members of the Nigerian Army opened fire on unarmed End SARS protesters at the Lekki toll gate in Lagos State, Nigeria, I wept. My body unbolted into doors; each one leading to a room of questions. Who gave the order? How many lambs were sacrificed for the purity of my country? Vellum or drum, what do they make off their untanned hides? If it’s a vellum, would it hold political or revolutionary poems? If their skins are stretched to cover a hollow wood, metal, or pottery, and then struck by a hand or stick, would it sound rather melodic?

The massacre stuffed withered roses in citizens’ mouths when the protest was nearly two weeks old. Lockdowns began in some states, in which some netizens vented their bottled anger on people of different tribes–– visitors or travelers. This was a bad time to be a lamb among lambs in wolf furs. Curfew was declared in some states, but some travelers were caught up on their way and had life the way of the Christ on a torture stake.

Enugu. On October 24, 2020, I was on a trip to Ibesikpo Ediam, Akwa Ibom State. I had promised my father-in-law to-be that I would be around to request for his daughter’s hand in marriage the following day. Enugu was peaceful until I left Abuja. There was no rumor about the chaos that enveloped the state, tossing it like a nylon in a gusty wind, until I got there in a Sienna with other passengers. There were barricades, 180 meters apart, on the federal roads by gamins; consisting of mostly boys in their early teens. While their godfathers sit in tents that look hurriedly built to give them shelter, the boys were collecting offerings from travelers before allowing passage.

Our driver like others cooperated until we got to a point and he refused to yield to the road keepers. He complained of how meager his take-home would be if he continues to dip naira in their hands. He had already wound down his side-glasses, switched off the vehicle’s air conditioner for fuel’ sake; the Sienna moving at tortoise’ pace, trailing some vehicles, while they take collections. They eventually halted us.

“Hausa! Hausa!” One of the emissaries shrieked.

There was an assemblage of three groups from their stations; clubs, machetes and guns in their hands, and running towards our vehicle. I saw for the very first time in my life, sophisticated guns in the hands of civilians.

“Where en dey?” an echoed question that sent a gravy chill into my body.

“See am here!” Passengers could see plenty fingers pointed at me, but it was swords I saw, aiming for my throat.

However, I smiled. It was to calm the storm raging my body.

“Kedu?” a man greeted to ascertain my origin.

I didn’t answer. I could have said: “Ọ dị mma, ekele! Kedu gị?” (I’m fine, thanks! How are you?) The mood I was, I had believed a force I do not know its origin would snap my words and make it sound like lafiya lau. I knew no god would save me if I utter anything in the language that portrays me a northerner.

“I––be–– Yoruba–– boy,” I said, calmly counting my words.

“Na lie!” One of them snarled, his voice–– a muezzin that nudged the mobs into action.

They attempted to possess me. But the vehicle had an automatic lock mechanism and wouldn’t give me out. They pulled the handle from outside but the door didn’t open. They began dragging me out of the vehicle through the side window. One of them dipped his hands under my armpit, the manner a child is lifted. I clawed the interiors, at least to buy me time for my last prayer. I told God that I wasn’t ripe for death. What would you have said to him at such moments?

One of them, a young boy I presumed was 15 pointed a double-barreled gun at me. “Make I just scatter en brain at once.”

“No now! Na to mob am be the best. Come snap en nyanma-nyanma body post for social media take trend,” another responded.

I thought of the people I loved in secret, my aunt who believed in me to make the family proud, my favourite cousin, Moji. I thought of the beautiful maiden I had promised to marry. She would get over it anyway, and move on.

I prayed. God, this death isn’t proposed for me. A death that calls for one to scream and scream for mercy in the hands holding clubs, smashing bones, meshing flesh to look irritating to scavengers. I’ve always wanted a peaceful death, voyaging beyond through siesta, after a sumptuous meal.

“My pikin, I take God beg una. Make una leave this boy alone. We dey joke since for road. Na good boy and na Yoruba en be?” An elderly woman said to the mobs.

“Mama, you na our mother. But we no go leave this guy until we dey sure say en no be Hausa?” the one who had gripped my hands and pulling me out, said.

I wasn’t sure if I wouldn’t have denied my identity if I was truly a northerner. The sight of terror was everywhere, spanning from a blood drenched police officer’s uniform on the ground to bullets and empty cartridge decorating the environment while boys were drinking, puffing smoke and shooting in the air at intervals.

“Mama, I swear, this boy no be Yoruba. E no hear wá síbí,” another one said. “See en head shape like mey ereke.”

I bleated, not knowing my fate: “Ẹjẹ́ ọmọ Yorùbá ni mí.” I am a Yoruba person.

“Enhen…! na now you come!” One of them said and I sighed, my breath pushing death away from me, into an abyss.

They wouldn’t let us leave without paying a ransom in exchange for my life. Isn’t that what Christ the lamb of God did?

“Oga, you go settle us before you leave…make men drink to your life,” one appearing to be their ringleader spoke from the tent.

So we all gathered from our purses to give to them.

While still there, I thought of how my death could have sparked a civil war. Insane, how few men could declare war by their actions. But it is the masses that would engage in it and get killed.

I left there, thinking of God’s wonders, and for the first in my life, I understood the idea that we are one in Nigeria is really a scam. What binds us together should be beyond national anthem, right? Believe me, I have no space in me for grudges against any tribe. My best friend remains a man from a different ethnicity.

You would think a massacre would be enough. That the blood on the asphalt of Lekki would satisfy the appetite of power. But history, like hunger, is never satiated. There was another protest soon, not against police brutality, but of a people crushed by daily living. Lambs returned to the street with ribs showing and stomachs echoing the absence of justice.

End Bad Governance

About the protest, I saw the news first on Facebook. It was slated for August 1 to 10, 2024. It’s a protest against hardship. You can call it “Days of Rage”, “Hunger Protest”, or the #EndBadGovernance Movement. Thousands of mostly young people poured onto the streets across Nigeria on Thursday as they protested.

Abuja. I was in my office in Kubwa-Abuja, when the protest began. What was meant to be a peaceful protest became chaotic on the Thursday it started. The sad news of a lamb dropped dead soon reached me, his corpse dropped in front of Zenith bank in Kubwa. And the flock moved on, marching for a better life.

On that day, there was a harvest of sad news: vandalism, looting, and violent clashes between protesters and armed forces which led to shootings. I heard gunshots but I had called it the bangs of fireworks. It was rumoured that civilians brought out firearms first. However, a special squad of police drove into our street and began shooting in the air. There’s mayhem in the street. I watched from my office, from a multi-storey building. There were so many movements, all happened at once that I couldn’t grab. The scene dug up all those memories I had of the End SARS protest. I remember seeing an old woman running into a ditch to escape a bullet. A young girl hawking groundnut ruptured her ankle. I presumed they knew their status as protest lambs. And in the case of being a victim of stray bullets, who do we hold responsible, the policemen or the government?

My heart jumped from the mediastinum into my mouth. I posted my epigraph on my Facebook wall.

A lamb slaughtered by his country

15 May, 1997 ––

I deleted it, quickly. I prayed to die another day, not by a bullet, not as a sapling.

***

I still walk these streets, sometimes whole, sometimes halved. I no longer chase shrines or vigils. But I carry them in my memory. Like all lambs who have lived long enough to remember the taste of mercy, I know this: safety is not a place, but a prayer that holds even when bullets fall.

Blessing Omeiza Ojo is a creative writing teacher and editor. He is one of Nigeria’s leading mentors of teen authors and new generation spoken word artists. He has received numerous honours including the Best of the Net nominations, 9th Korea-Nigeria Poetry Prize (Ambassador Special Prize), the 2020 Artslounge Literature Teacher of the Year award, the 2021 Words Rhymes & Rhythm Nigerian Teacher’s Award, the 2022 & 2023 HIASFEST Best Teacher Award, the 2024 Eugenia Abu/Sevhage International prize for creative non-fiction, and the 2025 Golden Award for Art Administrators. His works have appeared in Split Lip, Cọ́n-scìò The Deadlands, Roughcut Press, Olney, and elsewhere. Omeiza is a member of Hill-Top Creative Arts Foundation, Abuja. He takes great delight in leading teen creatives to literary festivals/competitions where they have won a lot of laurels including HIASFEST, ALITFEST, LIPFEST, and AIPFEST. When not writing or teaching, he enjoys being a father, balling and playing PES with his son or his friend, GP. He tweets @Blessing_O_Ojo. Check him on Instagram @ink_spiller_1.