In partnership with Alinea Initiative, Goethe Institut Nigeria, African & Black Creatives for Development, and SELDI, SEVHAGE presents the winners of the Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction 2024. Abasi-maenyin Esebre’s piece is the joint-winning entry.

I

I failed English in WAEC. The second time I wrote the exam, I got an E. And the third time, well, the third time is yet to come. Growing up, however, both my parents and teachers labelled me a prodigy. They had ample proof to sustain this grand consensus: my report cards, for example, often held unbroken ladders of A’s. Plus, I got promoted twice—from Nursery 2 to Primary 1 and from Primary 3 to Primary 5—and still managed to come first in the new classes with characteristic ease. If I had an unusual artistic intelligence for language, a talent for lucid, poetic prose, it remained dormant and unexpressed.

Since I showed a precociousness for math, everyone expected me to gravitate towards the sciences, which I did, a plan they hoped would end with me becoming a ship captain or a medical doctor. Even though the arts would eventually offer me purpose and direction, I revelled in the reverence from my peers, and dad, who doted on me for getting perfect math scores, just like he did when he was around my age.

In secondary school, the entire fanfare reached an envious crescendo when, due to continued academic excellence, I was granted a year-long scholarship in JSS 2. At this point, I showed a double affinity for fine arts and mathematics. As a result of being good at both subjects, I enamoured the respective teachers who, apart from exhibiting my still life drawings and calling me to solve SS1 students’ algebraic equations, were impatient to witness my future unfold in all its wild, prophetic promise.

Two years later, my fate turned. My artistic side was utterly crushed when my dad announced that I would be attending an all-science school. A legacy choice that mirrored his own childhood and further justified by my excellence in math. The repercussions for my passive aggressive compliance to this ‘unanimous’ decision came almost immediately: for the first time in over seven years, I came fourth.

II

Many prodigies are destined to become prodigal sons, legends that wither into cautionary tales. I acted out this epigram by dithering academically throughout the next four years and four schools it took for me to complete my senior secondary education.

In retrospect, it’s difficult to assign blame. Do I point to my inability to voice my disapproval for the school choice or hang the cross on my father’s calculated expectation? I, like most people, tend to trace blame from without. On the rare occasion where I admit half the fault, I turn the rankling guilt into a game of tennis and knock blame—the lemon ball, the very object upon which my false absolution is ruthlessly bargained—between my dad and I.

So, to nearly everyone’s dismay, the mere disturbing restlessness snowballed into complete and utter neglect for my studies. One by one, the good omens withered into regret, loathing, and shame. The aftershocks rocked my family: I came 7th, 8th, 12th; I skipped even more classes on a whim, setting everyone’s expectations ablaze overnight.

Then, as time passed, puberty delivered a double transformation to me. While my organs shapeshifted, my mind began to unravel in troubling ways: God fell out of my eye sockets, and my parents’ harmless dreams turned into an endless nightmare. I no longer fancied becoming a ship captain, as envisioned for me by my parents, and the prospect of becoming a medical doctor—suggested by my then pastor—filled me with aching dread.

As I nitpicked my identity down to my persona, as my doubt in Christian faith hardened into a stubborn atheism, as I sought out a profession I’d gladly sacrifice my youth to, as I gained admission to study Computer Science in Unical and continued to skip even more classes, I fractured into an alien yet familiar version of myself, like powdered sugar filtering down the neck of an hourglass. Overtime, I succumbed to my own thoughts, spiralled into depression, and dropped out of uni.

III

In botany, there’s a phenomenon known as guttation, where plants, and some fungi, use root pressure to release excess water accumulated overnight through openings on their leaves. My emotion cycle in the first few weeks and months before I dropped out can be summarized thus: I suffered endless guttation.

The pressure from being a disappointment, of losing faith in the religion I’d grown up loving and having no one to confess this to, in not knowing who I was or wanted to become, all that pressure forced tears out of my eyes at random hours when night fell.

I spent midnights curled in the fetal position, tears streaming down my face; I sat on soakaways and whimpered; I went on as many errands as I could to stay away from home, so I could run and blame the tears on the wind.

One night, tired of wetting my cheeks, I searched for the best way to end one’s life. After scrolling through different poison options, and sifting through articles that warned against jumping off skyscrapers, I stumbled upon one that recommended dragging a razor blade horizontally along the vein as opposed to just slitting the wrist. I promised to try the next day.

For some odd reason when I put my music on shuffle that night, Alive by Sia came on. I’d listened to it several times before then already, but that day I let the song listen to me; and it did: every single verse struck a chord; every belt, every voice break, every little aspect of the song reached for me and pulled me back to life. I was alone until she sang—her words, her aching, breaking soprano corked my bottomless despair.

I wept for want of words. “I’m alive,” I yelled in a strained whisper. I’m alive. The tears rolled. I’m still breathing. It felt cathartic to cry in the presence of another, even if that ‘other’ was a prerecorded ballad of a highly acclaimed pop singer. I remember that night as the night art saved me from death.

A few days later, I dropped out of uni when an epiphany hit me that I’d want to become a writer.

IV

When the mirror and the past could no longer tell me who I was, out of its many, many masks, art gave me a face enduring. It repaired my nakedness with music and prose. Baptised by the tears that coursed through the dead rivers in my palms, I returned to the world anew. Unafraid to pocket flowers and weep over sunsets again, I returned to the page and laid hard words like bricks.

I could dream again. I wanted—no, needed to express that I was already a writer. I carved my initials on a flame tree as a promise to master language. It didn’t matter that I’d failed English twice in my WASSCE, or that I’d never done literature in school, or arts in senior secondary either, a path from that moment snaked into the distant future. Then and there, my true education began.

Unlike most gifted children, my intelligence wasn’t borne on intuitiveness. The A’s I got came from reading my books multiple times over with makeshift lamps constructed from microphone batteries and deconstructed rechargeable torch lights. I spent hours every weekend solving all the math equations in the textbooks I owned.

Years later, when I picked up the guitar, my friends who I was learning with had a natural flair for the instrument. In contrast to them, I had to obsess over finger exercises for weeks before my palm could span the entire fretboard.

Given how insidious my loneliness was, how it insisted on fatal isolation, I vowed to become an artist—to learn to save myself, and others by extension.

Because, looking critically, there’s no popular melancholy equivalent to the stand-up show, an event where people gather to undress their depression. Pain is personal and depression insists on privacy. Oftentimes, the only way to get through to a lost person is through painting, literature, or music. Art is the air balloon suspended above the abyss, carefully positioned to catch the falling, the fallen, and the felled.

V

We cannot rehearse certain things in life. Neither the sweet yawn of love nor the bleak dawn of grief; neither losing a cherished job nor a relapse after four years sober; neither breaking down out of the blue or getting robbed on the eve of a loved one’s funeral. But the things we can rehearse—a dance routine, a poignant ballad, a staged play, a massive landscape painting—the things we can rehearse make the unrehearseable parts of life a little more bearable, beautiful, and even worth half the hassle.

This has been my guiding principle so far, the very reason I squander what little intelligence I have making poignant art. I hope to do with literature what Sia once did for me through music: make it known to the hurt, the lost, the weary that there is life after the life we leave, that a lost kite can function as a compass rose to a different set of weary travellers. For if anything is true about the broken, it is this: hurt people seek art.

And therein lies the beauty, the necessity, the very immutability of art. It redeems. It proffers identity. It dispels loneliness. Although one’s heart can also become one’s hearse, artists and their art exist to remind us that apples are born from cyanide, that others have suffered exactly as we have, that we are never as alone as we fear we are.

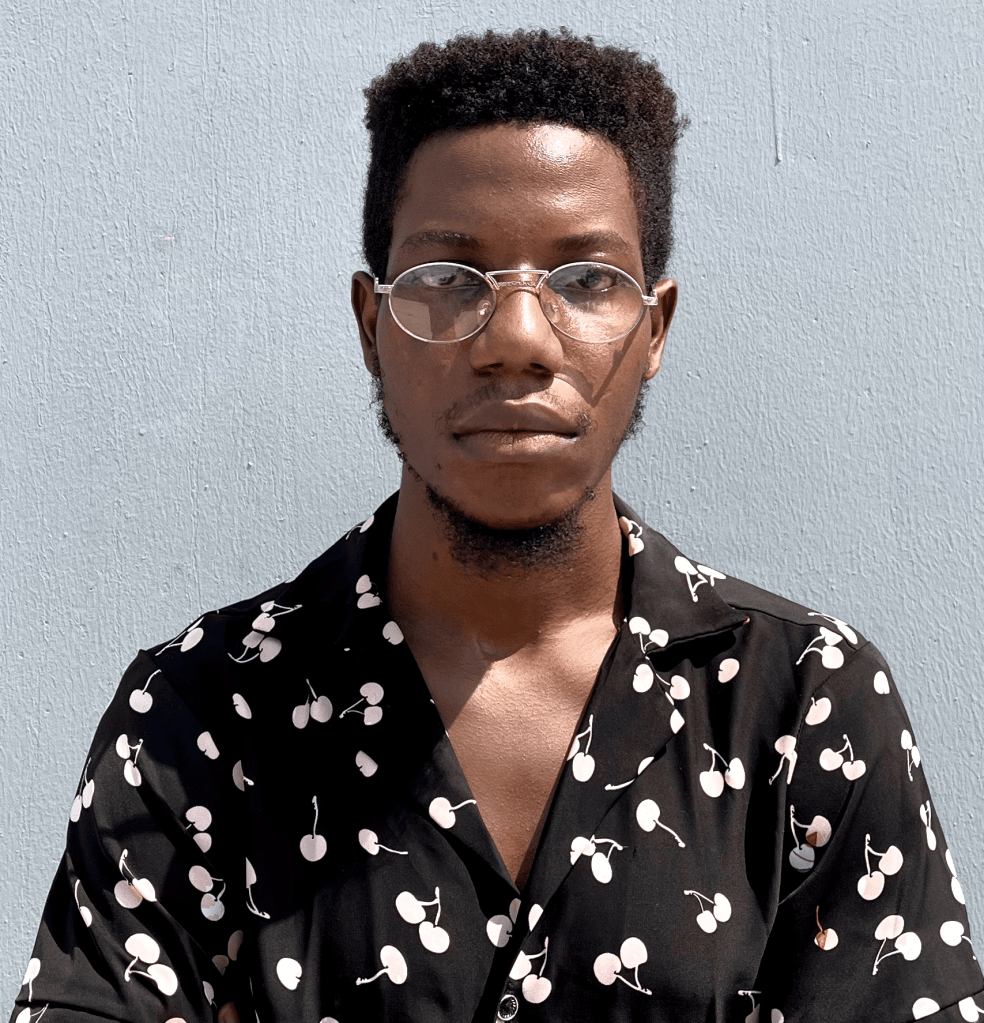

Abasi-maenyin Esebre is an Oron storyteller who centres Calabar, the city where he grew up, in his stories. His essay, Call Me By My Name, was published in AFREADA. He won the 2023/2024 Sevhage Prize for non-fiction with his essay, Grief: Its Invisible Gerund and Compass Rose respectively. His short stories have been shortlisted by Gratia Magazine and ALITFEST in separate competitions. Curious to a fault, he enjoys research in his free time and is an avid reader of both film and literary criticism. Although he enjoys writing books and aspires towards being an author, he plans on making a pivot to his original dream of being an auteur. He runs The Rich Writer’s Manifesto, a blog where he reviews books, and films. You can find him on X (formerly Twitter) @abasimaenyinn