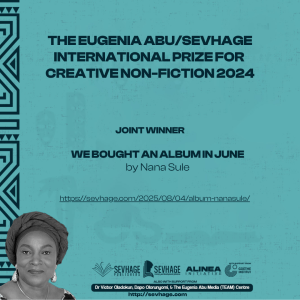

In partnership with Alinea Initiative, Goethe Institut Nigeria, African & Black Creatives for Development, and SELDI, SEVHAGE presents the winners of the Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction 2024. Nana Sule’s piece is the joint-winning entry.

We bought an album in June. In the first picture it housed, I wore a wide smile, a blue gown, and a white veil tied in a bun over my full hair. It was the time of year when the rains started to fall with a little more rigour. And if you looked closely, past the henna on my feet, you would see the rubber slippers I wore — ugly, flat, efficient little things. We had come in from a drizzle, as though the skies looked down upon us in awe and blessed us that day. The little camera was there on the kitchen cabinet. Standing by the kitchen door, we captured our happiness in a click. In that picture and the many pictures that we included in the album that month, I had both hands hovering softly on my stomach. I didn’t know you then, but it was enough to know you were a part of me, enough to propel me to want to keep you safe.

We bought an album in June but by early July, the pictures of me on my feet had dropped to a lento. On one fine sunny Saturday, we went shopping. I picked a cute little shoe from the Babies section. It was grey, with soles of black. Your father and I argued about babies and colors.

“Babies need to have colors, that’s the way you stimulate them, help them navigate the world.”

“My baby will not look like a rainbow fell on him. He’ll look dignified, chic, and prim in monotones and beige.”

“How do you know he is a he?”

“I just know. Like I just know he doesn’t like colors.”

I should have listened to your father. When we returned to the place you should have called home, you squeezed out a little color from within. A little red on the white bedsheets where I slept. Click, click, click, and we had pictures of the shoes, a reluctant selfie at the hospital waiting area, and a picture of me in bed with an orchestra of medications on my bed stool. And a smile that did not reach my ears. There were no pictures of me standing in August. Instead, I sought hope in verses of the Quran. I had them printed, cut, and reduced to size to fit into the album.

and your Lord is going to give you, and you will be satisfied

and your lord does not burden a soul more than he can bear

and your lord is ever living, self-subsisting

and your lord is nearer to you than your juggler

I engaged in conversation with my Lord, summoned him in my head, had an agreement with him. I would serve, I would obey and in return, he would give me you. I deserved you. I had prayed, fasted years to carry you, willed you to live and if life must collect its tax, then let it be me. I took more progesterone pills, willed my body to take hint… to make more progesterone, damn it! But click and there was a picture of me your father caught, legs propped on pillows, henna-less feet, a smile mirroring the fears in my eyes.

At the end of September, there were two pictures added to the album. In the first one, a doctor is bent over me. Your father caught her at the time when her fetal doppler was on my open, rounded belly. In that picture — and because your father had randomly shouted “cheese” — we both looked into the camera. Click and there… subtitles of worry the doctor failed to hide on her face and the rascal fear that wore itself on mine.

“It’d be alright,” your father said.

I knew it was not going to be alright. I already felt you pull away from me, felt you say goodbye. There is no way to explain that I was connected to you long before your heart started to flick on a screen, no way to tell that I knew, even as the doctor tried and failed to be reassuring, even as he ordered more tests, you were already gone. I knew.

When they finally announced that you were out of breath, my legs were opened on the radiologist’s bed. He had performed a transvaginal pelvic scan. There were beads necklacing both ovaries, the culprits who prevented them from producing the progesterone you so desperately needed to live. Confirmation of my failure. It was no fault of yours. It was this body that could not keep you. It was the fault of my Lord who gave me this body that couldn’t do a simple woman thing. I recall placing that last picture of your static body swimming lifelessly in the waters of my womb, in the album and just looking at your tiny frame. As your father rubbed my back, portraits of the life you could have had circled in my head. You, in my arms, you sitting, crawling, walking, fitting into those shoes, fitting into our lives. I remember laughing, laughing till my stomach started to hurt, till I sank into a deep sleep.

It took two weeks of October to convince me to return to the hospital. I befriended hours of troubling sleep. In those sleeps, I had dreams of my Lord. I told Him, I was holding on to His miracle.

“I need you to do this for me. Please, bring him back.” I pleaded.

More progesterone went down my throat. I kept propping up my feet but each trip to the bathroom to pee produced more clots of brown and red. You were disintegrating. You were separating from me, your mother! But I was your mother and I did what mothers do: I waited and hoped and prayed until my faith thinned and I finally, much to your father and your grandparent’s relief, sat to face a doctor.

“We can give you a pill — “

“No pill, take him out now!”

“It’s just safer to start with a pill.”

“I can’t wait anymore. I want him out of me now.”

I wanted you out. I hated you for not staying. Why didn’t you stay?

We set up in the ward that should have been the place I labour for you. The doctor began by inserting an instrument whose name I do not know into my vagina to dilate my cervix. Then bit by painful bit she began the task of our separation.

I began to cry. The cry started from my stomach, climbed into my oesophagus, and leaped from my mouth in a wail. I cried. Your father’s hand stroking my hair did not console me. The pain medications did nothing to take the pain away. Because it was more than a physical pain. It was the pain of amputation, of the dismembering of a part of me I could not retain. A part of me that should have been prim, proper in monotones and beige.

Later, the Doctor prescribed medications against potential infections. She said therapy too, alongside an appointment to treat the underlying problem. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. PCOS.

“You were very lucky to conceive this one. You should be grateful that at least we can start medications on time and help you conceive and carry others to term,” she said.

Others. As though you were replaceable. As though a child is a bulb hanging from a ceiling, something to replace when the light burns out. I listened in a daze. I pushed myself to a field of flowers where the world was sunny and you laid with me in the grass and your name was Noor. There was only one picture from October in that album. It was the one we took a week after you left me. An evidence for your grandparents, to show that I and your father were doing okay.

I cut my hair in November. Your father said it looked very sexy so he clicked away. I posed this way and that. In a moment of forgetfulness, I cradled my stomach and remembered. Maybe it was a force of habit or maybe it was because you would always be a part of me, somehow. My smile came undone. We hugged, your father and I, before I told him that I needed to forget.

He stopped taking pictures of me. He hid the camera. He hid the album, the baby shoes, that bedsheet with the first stains, he hid everything, but I could not forget. Because you see, there’s a different kind of pain in remembering how everything failed to hold me together. My Lord failed me, you failed me, my body failed me, your father failed me (don’t ask, I don’t know how), and I failed me. I failed to shield my heart from hope and remembering. And sometime in the last weeks of cruel, cruel December, I became resolute in my determination to forget you, I tried to pinpoint the moment where you did not exist, where you did not matter. I remembered the album, the clothes, the bedsheet, the medications, I remembered everything.

I went on a hunting spree. I searched. The house became a pocket I turned out till I found the items I needed. I gathered every trace of your memory in a pile outside. The album sat at the head of it. I drenched them in holy petrol, then set the witnesses to your existence alight. As the flames grew, a part of me rose to the sky with them. For a moment, I think I saw you smiling in the clouds.

NANA SULE is a writer, journalist, and communications strategist. She curates literary events and co-owns The Third Space, a bookstore and workstation in Kano. Her works have been published in Agbowo, Isele, SEVHAGE, Arts-Muse Fair, and elsewhere. She is a joint winner of the Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for

Creative Non-Fiction (2024) with her exceptional piece, ‘We Bought an Album in June.’ She was also the first runner-up for the ALitfest Prize for Fiction (2022) and was longlisted for the 2023 SEVHAGE Prize for

Fiction for her short story, ‘Owanyi.’ Her essay, ‘Birthing the Mother’, was a notable essay in the Abebi

Award in Afro-Non-Fiction (2023) and was published by Isele Magazine. Nana is the author of the collection, Not So Terrible People, was published by Masobe Books in 2025 to great acclaim. Nana aims to craft stories that feel familiar yet imbued with the unexpected. She also indulges in a love for chocolate.