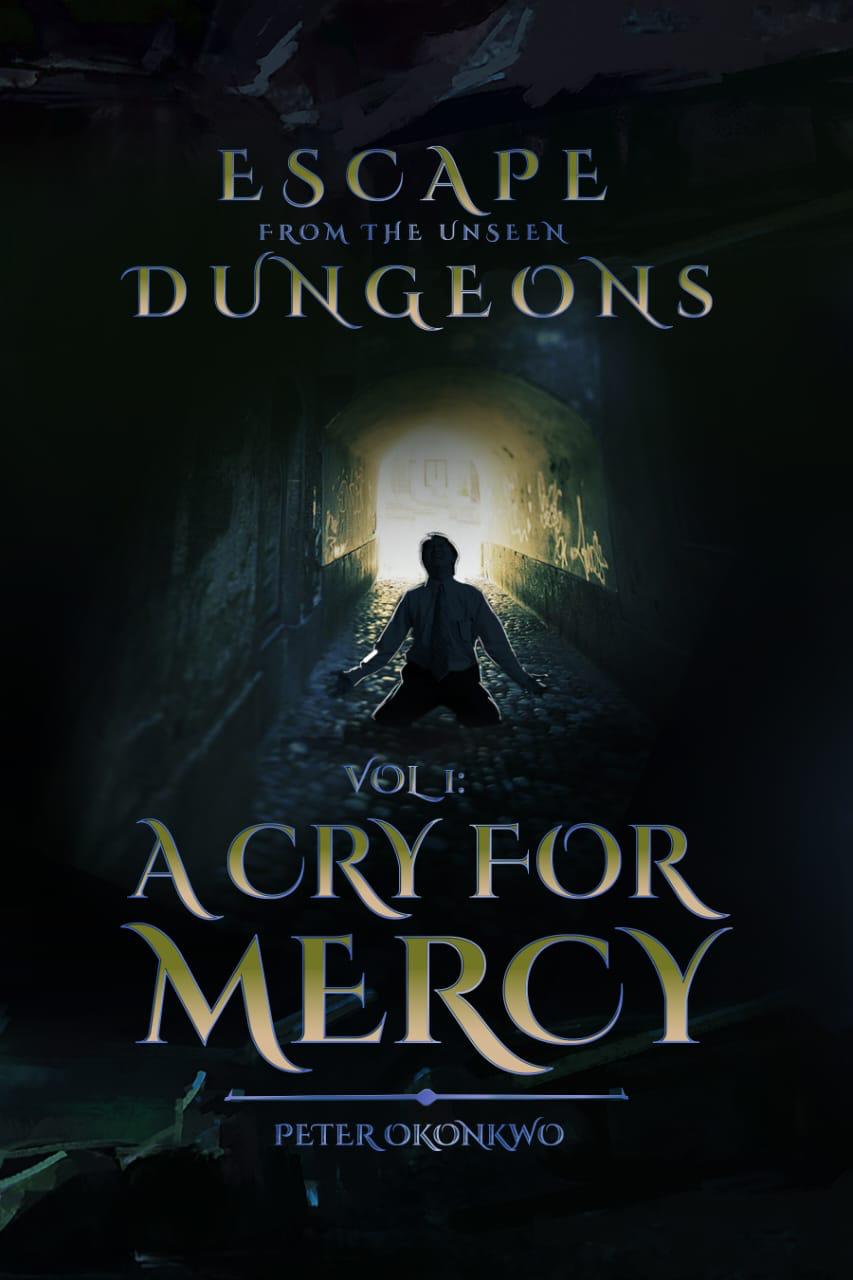

A Cry for Mercy is a book of lamentations. A distraught persona navigates mystical terrains with a carnal compass—interrogates pain from a spiritual slant. This 123-paged poetry book is a collection of letters to God. It’s like a diary—frustrated monologues & aching contemplations—mistakenly left in the open. Who writes letters, you wonder, in this age, especially to an all-knowing God?

A poem is a prayer. In Longing for Help, like most of the poems in this anthology, the author uses repetition reminiscent of a prayer session on the mount. I imagine restless pacing & a vigorous shake of the head. The poet persona admits his helplessness & calls on a higher being. There are some mountains/that I cannot climb alone, he concedes.

The book opens with the titular poem, & similar to the Biblical Psalmist, Job & Jeremiah, the poet seeks the face of God. Peter Okonkwo’s lines depict a soul lost in darkness—desolate & desperate. Dear Merciful God is repeatedly used in this poem, perhaps to access the soft side of the supreme being, appease the light.

The actual source or nature of the character’s pain eludes us in the long verses of this collection. The poet only gives us a key-hole view of his grief with an array of dark, abstract lexis—tears, anguish, sorrow, trouble, cage, obstacle, delay, shame, bondage, oppressor… It’s like driving in circles or a ball rolling around the rim but refusing to fall through the hoop. With this, you could say Peter is able to transmit his frustration to the readers.

Like A Snatched Destiny makes an effort to give a glimpse of the poet’s pain, it’s yet shrouded in mystery: I am dying of a sickness/I don’t know its source. This second poem helps to amplify the confusion of the writer with a myriad of enjambment, a thread of contrasting thoughts & unending rhetoric. The poet begs for healing & in the same breath seeks a rope of suicide/so I may hang/myself on the/hopeless tree… In Comfort to my Dead Self, he questions, why should I keep living/when I cannot live? & a few lines later he switches mouth, do not let death/comfort me. The emotions are a wild seesaw.

My interest in literary obscurity makes me wonder if this is the path taken by this author, but the aim for vagueness here leans more to context & emotion rather than language or imagery. Obscurity, according to Daniel Tiffany, is the art of disappearance. This poet persona wishes his pain—or himself—to vanish rather than actually confront the demons.

It’s natural that when things go wrong we want to identify the cause, perhaps find who is at fault. Sometimes, it could be the need to pass the blame, find a scapegoat—in this book, the devil is the easy culprit, as well as fate & destiny. But Peter Okonkwo didn’t absolve himself, assuming he & the persona are the same, of the blame. Like Job or David, he strongly believes he’s afflicted because of his sinful ways as we can see in poems like Forgive Me, I Surrender It All, The Wretchedness of a Filthy Man & more. A Soul At War seemingly captures all the guilty parties: The flesh you gave me/rages war against my soul./If my dearest soul loses/this fight, what will be/the fate of my body?/And if my flesh loses/its spirit, who shall I blame?

In this book, pain is pedestrian. It is repetitive & resolutely unspecific. A reader may be unable to key into the poet’s emotions because the verses are almost devoid of concrete narratives. The poems can be leaner & sharper, pruned of unnecessary devotion to raw thoughts as a tool to achieve sentimental depth. Peter’s poetry would become a notch more intense if enhanced with metaphors & a hint of vulnerability.

—

Jide Badmus, poet and editor, is the author of the poetry collections, Scripture and Obaluaye. He lives and works in Lagos, Nigeria.