Number of pages: 111

Publisher: Cookingpot Publisher

Place of publication: Jackson, Tennessee

Year of publication: 2024

Genre: Children’s Literature

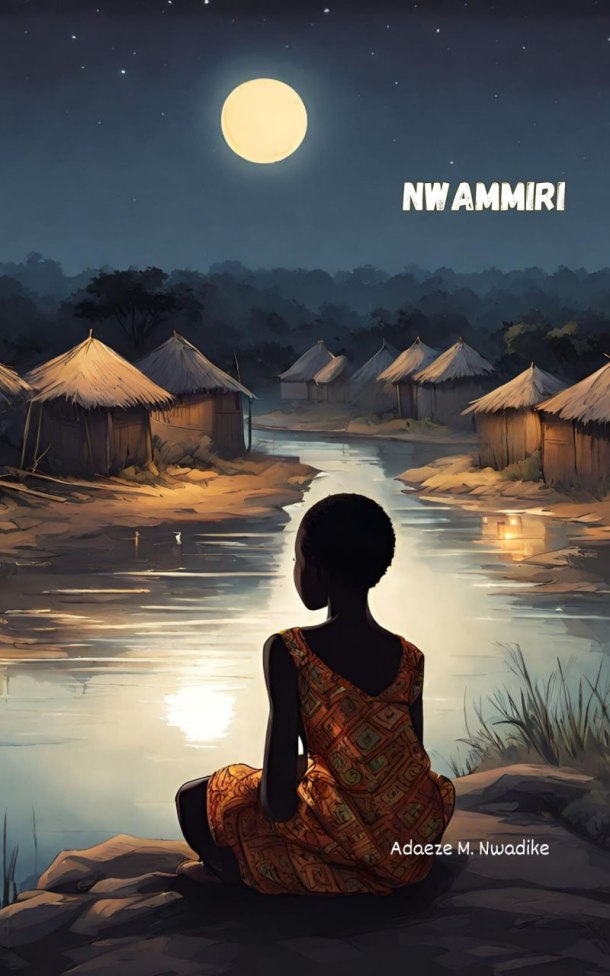

With a story built on the innocence of children, siblings scuffle, and every banality of human existence in its beauty, a single switch, which begins with the contamination of a river breaks everything. Friendship tore apart, and a density of uncertainty decked every family’s life.

Osu River has been a string of the people’s history; they worshipped it before the arrival of the white man and relied on it for economic activities—being mostly fishermen and traders. Kanma, who is nicknamed Nwanmiri—child of the river, does not know what calls her to the water but finds herself always going back to it despite the warning from her parents: “I forbid you from stepping foot by the river again. Your umbilical cord was not buried there. Her mother would threaten” (7). Typical of the African belief that the place where a child’s umbilical cord is buried has a relationship it fosters.

But the eleven-year-old Kanma already has an affinity with natural elements, which shows her reason for loving the river: “There was something about the river that pulled her in. It was possibly the way the trees by the path towered so high and set a canopy above her head, or the chirruping of insects and bird songs that made her giggle as she walked to the river” (7). There is no politics attached to her belief, it is a child reeling the innocence accompanying being a child who lives in the village.

Showing a rural way of living, Adaeze Nwadike builds on the order that exists in families, schools, and churches, and its interconnectedness. With all of Aninta’s imperfections, and despite not being on the map of developing places, the people are comfortable. Although typical of most rural places, there is always a call for migration to cities which are more cosmopolitan and believed to hold better promises. When Kanma’s Uncle broaches her father to relocate, he dislodges it with the belief that he has everything that he needs in the village. But the story takes a switch with the discovery of oil in the village.

Adaeze shows the growth of the entire village, and its ballooning from being a rural place of comfort for its inhabitants, and the encroachment of plundering which comes with ‘discoveries and capitalism’. Before the discovery of oil in Aninta there was contentment, which was soon shattered once crude was found.

One day during an emergency assembly, the Head Mistress nicknamed Miss Koi Koi announces that the “River has been nothing but kerosene and mud. Is that what we shall cook with and drink? Who among us does not benefit from the river? Has Osu not been generous enough?” (62). From the headmistress’s speech, Adaeze projects what I believe is one of the crucial aspects of African eco-criticism, which is the involvement of nonhuman agency in the discourse of ecological issues in African literature. This pattern which embraces the African system of worship shows how everything is interconnected, and this shows an aspect of the decolonial struggle to break away from colonial pedagogy.

With the navigation towards decoloniality, authentic African discourses refuse to succumb to the narrow view of Euro-American claims of rationality. African scholars are speaking on a framework which encompasses transcendental materialism—an interstice where people’s metaphysical beliefs and their relationality with the material realm converge. The way Adaeze gives Osu River a life of its own, through the Head Mistress, despite representing the beacon of Western education by personifying the river, shows how people’s beliefs are crucial to ecological perseveration. At the assembly, the headmistress says, “Has Osu not been generous enough? Do we wish to stir her rage? Yesterday, I heard over the radio that the flood has destroyed so many nearby communities. If we keep offending our river, maybe the wrath of nature might be unleashed on us” (62).

Sule E. Egya speaks to the above concern in “Out of Africa: Ecocriticism beyond the Boundary of Environmental Justice” where he notes that:

[the need for a shift in] paradigm by foregrounding a narrative that stages the role and agency of nonhuman and spiritual materialities in practices that demonstrate nature-human relations since the pre-colonial period. I argue that for a proper delineation of the theory and practice of ecocriticism in Africa, attention should be paid to literary and cultural artefacts that depict Africa’s natural world in which humans sometimes find themselves helpless under the agency of other-than-human beings, with whom they negotiate the right path for the society. (66)

In Adaeze’s Nwammiri, Osu River is such an agency. What is more intriguing is the way she asserts the past of the river, which still holds an influence judging by its having a custodian, its economic impact, and for the children, the beauty that comes from being around the water.

Children’s Heroism, Environmental Degradation, and Notes on Hope

Nwammiri introduces Officer Johnbull, a village vigilante who started with his desire to protect the village but was later made official by the village chief. After the ruin of the river and every family started leaving, Kanma, on her journey to the river for a final goodbye, before she leaves for the city, encounters Johnbull and his boys who kidnapped her to protect their secrets. She finds out that it is their discovery of oil and illegal mining that contaminated the river and made the village inhabitable. With a stroke of luck and intelligence, she manoeuvres her way and eventually gets them arrested.

What interests me about the way Adaeze crafts her story is how she navigates the plot’s build-up from children’s innocence and its connectedness to the environment. The story is not preachy because we see how the environment affects everyone’s life. The book achieves a show of children’s heroism. Kanma’s daring to push, not only escaping but tying ropes to ensure she remembers the path to Johnbull’s hideout shows she is deliberate in being a causal to the good of her society.

Because Illegal mining affects us a lot in Nigeria, the book, in its simplicity, shows how we can all take part in saving the environment. What is more absorbing is the hope that comes with the optimism of Kanma’s victory.

Oko Owoicho, poet, scholar and Admin Lead at SEVHAGE, lives and writes from Abuja, Nigeria.